It is so disappointing that Presbyterian Church in Ireland would appoint a moderator who asserts that women should hold lesser roles than men in the church. Sadly this is indicative of a wider problem in Christianity. Beliefs and practices that marginalise women are highly damaging to the church as a whole, especially when platformed and espoused by clerical men in power.

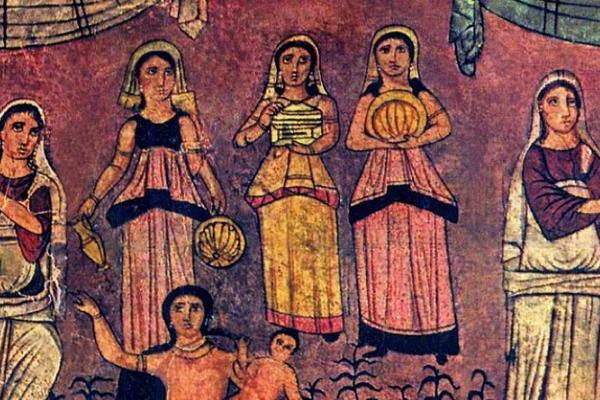

It’s not as if the lessons haven’t been there from the very beginning, even from the book of Exodus.

The story of Exodus opens with the salvation of Moses. By all rights Moses should not have survived his infancy. That’s because Pharaoh, afraid of the growing Hebrew slave population, had ordered that all new-born Hebrew males should be killed.

But then there’s an intervention. Initially, the Hebrew midwives refuse to comply with Pharaoh’s orders. Instead, they concoct a story that “Hebrew women are not like Egyptian women; they are vigorous and give birth before the midwives arrive.”

Then, Hebrew mothers begin to come up with other creative ways to save their children. We’re told that Moses’ mother hides her baby from the Egyptians for as long as she can, and then eventually she sends him down the Nile in a basket. But he’s not alone. His sister follows at a distance and keeps an eye on him.

Moses is then discovered in the river by Pharaoh’s daughter, who realises what has happened and “takes pity on him”. Meanwhile, Moses’ sister appears on the scene and offers to “go and get one of the Hebrew women to nurse the baby”. Of course, the “Hebrew woman” she has in mind is Moses’ own mother – and against all the odds, the plan actually works and the child is saved.

What a genius intervention from intelligent and resourceful women who are driven by compassion to outwit and to frustrate the whims of brittle men afraid of losing their grip on power.

Right at the beginning, the author of Exodus wants us to see how the resilient and compassionate sisterhood of midwives, mothers, sisters and daughters stands in sharp relief to the assumed privilege of patriarchal power structures.

This contrast is highlighted even more starkly in the very next passage. When Moses sees a fellow Hebrew being abused – we’re told he simply “killed the Egyptian and hid him in the sand.”

None of the compassion, creativity, resourcefulness or cooperation that we saw from the women in his life. Just impulsive, brute force violence fuelled not by compassion but by anger.

This predictably ends badly with Moses being instantly found out. He then has to “flee to Midian” and start his whole life over again in a new country. It’s almost comical how the two styles of intervention are shown to contrast with each other.

There’s a lesson here right at the start of Israel’s salvation from Egypt. It reminds us how those with little or no agency in the power structures around them often develop surprising creativity and resourcefulness in challenging injustice.

When combined with love and compassion, the results are world changing.

This is the sacred power of defiantly compassionate leadership which the church so desperately needs to learn from – and which is still coming from the women in our churches.

It isn’t even a case of “letting” women lead, because their leadership is not for anyone else to deny in the first place. If only the church’s inherited patriarchal power structures would repent and humble themselves enough to see it.

(Feed generated with FetchRSS)